Graduate School Makes Commitment to Data Transparency

Joining the Coalition for Next Generation Life Science

Originally published in the Cornell Chronicle

President Martha E. Pollack has committed the university to a new multi-institution initiative to make public data pertaining to career outcomes for life sciences doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers.

Specifically, nine universities and one research institute announced the Coalition for Next Generation Life Science in a policy article in the Dec. 15 issue of Science, authored by each university’s president or chancellor. Data collection will focus on the biomedical/life sciences research arena.

“This vital information will allow doctoral students to make informed choices about their careers,” said Pollack. “It will save them valuable time and give them the facts they need to consider when choosing their graduate program and career field, and it will help prepare them to compete for positions within and outside academia.”

The information will help students evaluate career options early in their graduate training and thereby prepare for a range of possibilities, the article states. In the biomedical sciences, federal research funding declined by 20 percent from 2003 to 2016, and only 10 percent of Ph.D.s in the United States land tenure-track positions at U.S. institutions five years after graduating. Lack of data has led to a glut of doctoral candidates who have trained for just a few academic positions, without considering the range of opportunities outside of academia, including industry, entrepreneurship, government and science communication.

The data to be reported across the coalition include:

- admissions and matriculation data of doctoral students;

- median time to degree and completion data for Ph.D. programs;

- demographics of doctoral students and postdoctoral scholars by gender, underrepresented minority status and citizenship;

- median time in postdoctoral status at the institution; and

- career outcomes for Ph.D. and postdoctoral alumni, classified by job sector and career type.

“The effort for data transparency is important to give – particularly prospective students – a realistic idea about what to expect in Ph.D. programs and in the possible career paths they can pursue following a Ph.D. or postdoctoral training,” said Barbara Knuth, dean of the Graduate School.

The information also helps to improve individual doctoral programs. “Here at Cornell, we’ve been sharing and comparing these kinds of data with our graduate fields internally, and that has driven our graduate faculty to strive to improve their programs. We’ve also already posted some of these data publicly,” Knuth said.

Currently, few research universities publish such data, partly due to cost, satisfaction with the status quo, or fear that institutions that post data will suffer compared with universities that don’t post data, especially if results appear unfavorable. For the few universities that do publish their data, there is a lack of uniformity regarding categories and formats of information across universities, which restricts the scaling of the data nationally, the paper states.

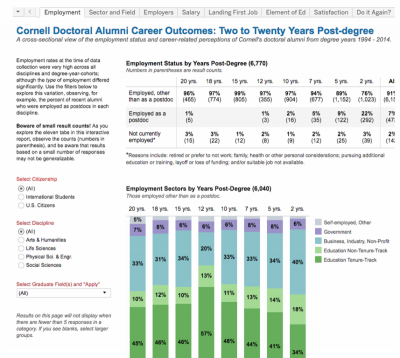

Promoted by Knuth, Cornell’s Graduate School has made university-wide field metrics publicly available since 2012, including data on applications and yield, enrollment, attrition and completion, Ph.D. outcomes, median time to degree and job placement. The data are filterable by degree type, discipline and graduate field of study. To meet the requirements of the coalition, Cornell will add demographic information and postdoctoral data.

Since 2014, the Graduate School has publicly posted Cornell alumni career outcomes, two to 20 years post-degree, based on research and survey results.

“We must be training and educating our students to be versatile to succeed in a variety of different career paths,” Knuth said. “We’re hoping that other schools will step up to the plate and do this as well; we’re trying to lead by example.”