Faculty Who Failed Series: Suzanne Shu

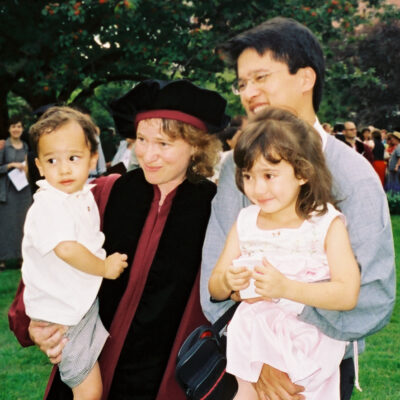

Suzanne Shu in graduate school

November 6, 2023

Graduate school is a time for students to push themselves, try new things, and explore. It’s also a time when students are likely to experience what feels like failure. These small or large challenges along the way to your degree are to be expected, and most faculty members experienced such stumbles themselves in graduate school.

To share stories of successful people who have overcome the setbacks that come with pursuing a graduate degree, we’re interviewing faculty members about how they “failed” in their academic careers. The Faculty Who Failed series highlights how resilience can carry you through the tough times in your degree program and come out of the experience stronger and better prepared for future challenges.

Read about S.C. Johnson College of Business Dean of Faculty and Research and John S. Dyson Professor of Marketing Suzanne Shu‘s experiences.

Can you describe a time you felt like you failed in graduate school? This could be a time when an experiment didn’t work out, you considered leaving (or did leave) your program, etc.

I felt like I failed a lot in graduate school. I was always a good student in regular classes; I do well at turning in assignments and reports with a deadline, or at studying for an exam. But when graduate school transitioned from coursework to self-directed research, I struggled. I thought running experiments and turning them into a paper would happen faster than it actually did.

The moment I really failed was at the point of my dissertation defense (in Cornell terms, the B exam). My advisors were very hands-off on the actual experiments or the writing process and so they hadn’t provided much feedback before the moment I stood up and presented my work. The feedback at that moment was brutal. I failed the defense, but I was given a chance by my advisor to revise it and try again. Several months later, the end result was not anything amazing but it was finally enough to allow me to graduate.

How did you bounce back from your perceived failure, or what got you through to the other side?

Luckily, at the time I failed my dissertation defense, I’d already accepted a job as an assistant professor to start in the fall and thus I was highly motivated to rework the dissertation into something the committee would accept. My mother took over watching my kids for the summer and I spent all day every day working on the research. I’m also grateful that my advisor’s new goal for the dissertation was to create a roadmap for future research projects rather than an immediately publishable paper. I was able to turn that dissertation roadmap into several publications over the next few years.

What lessons did you learn from this experience?

One thing I learned was the distinction between a big picture research question and a narrower set of studies that test a very specific hypothesis. I had been approaching the dissertation as if it needed to solve a really big problem. But now I understand that making progress on those big problems sometimes takes an entire career as an academic. Almost 20 years after graduating, I’m still working on different aspects of the big problem I was trying to tackle back then. While it’s OK to use the dissertation to set up the dimensions of the problem, the experimental work needs to be more tightly defined. A publishable research paper (at least in my field) will usually focus on a narrow element within the much larger problem. If I had focused on writing publishable research during my dissertation then I would have gotten off on a stronger foot as a new professor.

How did you use this experience to become better at what you do?

The experience definitely shaped the type of advisor I am today for my own graduate students. First, unlike my own advisors, I try to meet every week with each of my students to talk about the hypotheses they are testing and their experimental designs. I’m there each step of the way as a mentor and colleague to help develop the research. Second, I encourage them to think about the big picture for their research ideas while simultaneously pushing them to create tightly defined experiments. Learning to simplify the research question into a clearly testable hypothesis isn’t always easy; it requires controlling a lot of different factors while you attempt to study one particular relationship between the variables of interest. Finally, I try to help them finish their degrees with a clear roadmap of how their big picture research question can spawn future new projects so that they have a path forward as a productive researcher. While finishing the dissertation and publishing the first paper is important, having a successful academic career also depends on having a stream of additional future projects to keep you busy for the next few decades.

What advice do you have for current graduate students who might be struggling or in a comparable situation?

I always suggest to graduate students the importance of perseverance. There are going to be so many highs and lows in this adventure. On a small scale, there will be times you email a faculty member to set up a meeting or get some feedback and they don’t reply, and you’ll need perseverance to email them again until you get what you need. Or an experiment or analysis won’t work out the way you planned and you’ll need perseverance to rethink your design and try again. On a larger scale, there will be times when a research presentation (or even a dissertation defense!) goes poorly and you’ll need perseverance to revise it until it comes out better. Or a paper you submit to a journal will get rejected and you’ll need perseverance to revise it and keep sending it to new journals until you find the right outlet. This can be a long research career and while each disappointment feels huge at that moment, if you keep persevering, it can become just one more story you tell your own graduate students a few decades from now. Hang in there, and good luck!